Snow reveals Italy’s water future: what the 2024–2025 winter taught us about seasonal reserves

Image: PeopleImages.com - Yuri A/Shutterstock.com

Every winter, the CIMA Research Foundation conducts continuous monitoring of Italy’s snow accumulation across the landscape, tracking its quantity, distribution, and seasonal trends. This isn’t just a scientific exercise: it’s a strategic operation that helps forecast how much water will be available in the months ahead, when it’s most urgently needed for agriculture, hydropower, and domestic supply. Snow acts as a water reservoir, accumulating in winter, then melting gradually to feed rivers, lakes, and aquifers throughout the spring and summer. Monitoring it carefully is key to understanding how resilient Italy’s water system will be during increasingly hot and dry seasons.

Throughout the 2024–2025 winter season, snow monitoring by the CIMA Research Foundation revealed a climate picture marked by imbalances and anomalies, with major impacts on Italy’s water reserves. This systematic observation, based on meteorological models, satellite data, and ground-based sensor networks, made one thing clear: Italy faced a winter with significantly below-average snowfall, especially in the Apennines, a trend with serious implications for agriculture, energy production, and potable water supply.

The season started off slowly: early snowfalls were scarce, despite colder-than-average temperatures. This combination of dry air and cold weather prevented the formation of a stable and abundant snowpack. As early as December, data showed clear signs of snow deficits, especially across the central-eastern Alps and the Apennine range. The snow cover anomaly map from late December revealed large areas in northern Italy that were well below the expected levels for that time of year.

By February, the situation became even more complex. While northern regions, where most of Italy’s water originates, continued to experience a severe lack of snow, parts of central and southern Italy saw increased precipitation, mostly as rain.

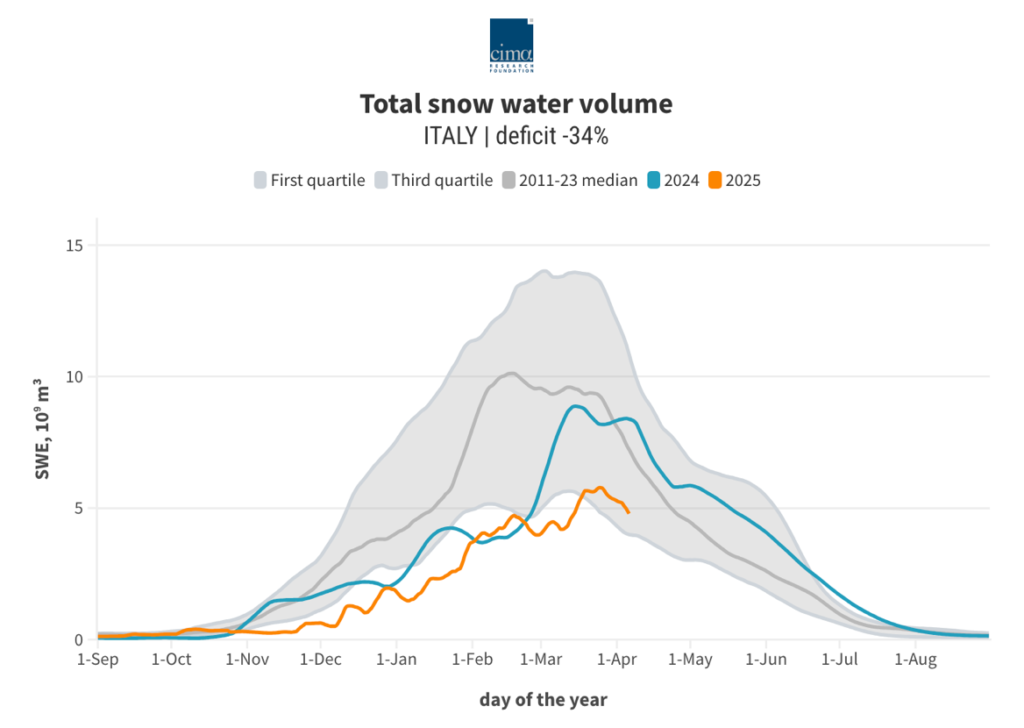

By March 2025, Italy was still facing a 57% national average snow deficit compared to historical norms. The Apennines remained the most severely affected, with extremely low values and virtually no snow cover in some areas. The central and western Alps performed slightly better but still fell below critical thresholds. However, as the season progressed and further snowfall episodes occurred at high altitudes, the national Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) deficit closed at -34%.

In April, the focus shifted to the melting phase of the snowpack, a key moment when solid water becomes liquid and replenishes key reserves. According to CIMA’s data, this year’s melt occurred earlier and more rapidly than usual, often triggered by sudden warm spells. This kind of melt is less efficient: water doesn’t have time to infiltrate slowly into soils or recharge aquifers, nor does it gradually fill reservoirs and lakes. Instead, it can cause brief, unusable surges in streamflow, followed by rapid depletion of reserves.

Practically speaking, this translates into less water available during the summer months, precisely when agriculture is in full swing and water demand peaks. Crops such as cereals, vegetables, fruit, and fodder face a serious risk of water stress, compounding the difficulties caused by previous dry years.

Amid this already fragile context, another vulnerability stands out: Italy’s glaciers, which is described as “sentinels of water.” In a dedicated analysis, the foundation highlights that alpine glaciers are shrinking at alarming rates. Glaciers serve as natural water reservoirs, slowly releasing their content in summer and helping sustain rivers and hydropower production. As they shrink and recede, Italy’s ability to cope with prolonged water shortages diminishes significantly.

The combination of snow shortages, early melt, and glacial retreat have to be monitored for Italy’s water future. These are not just meteorological phenomena, they are structural changes that affect agriculture, cities, energy production, and alpine ecosystems alike.

This is why snow monitoring, at the core of CIMA’s research, is becoming ever more critical. It’s not merely an observational activity, it can be decision-making tool for governments, farmers, water managers, and citizens. In a changing climate, every winter must be seen as a predictor of what’s to come. Snow is not just part of the winter landscape; it’s the water of the future. And that future demands sharper insights, quicker actions, and stronger resilience.